Bridges: Bridge Builders Under Threat

Recent rumors suggest a potential transformation of the G7 into the G5, retaining the United States and Japan and withdrawing the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Canada, and Italy. This shift would incorporate China, India, and Russia into the new group. In summary, it seems the objective would be to replace a bridge that previously united seven powers with one that unites five. One can surely ask: to what end?

Bridges do not merely connect geographies—they link eras, cultures, economies, emotions, traditions, and values; in short, the movements of time and life itself. Etymologically, the Spanish word “puente” (bridge) derives from the Latin "pons," “pontis,” meaning literally “passage” or “crossing.” The Latin accusative “ponte” gave rise to the Spanish puente through the diphthongization of the short tonic “o.”

As a Semitic legacy, “puente” (bridge) arrived in Rome not only as an engineering feat but also as a religious symbol: the "pontifex" was literally the “bridge-builder” between the human and the divine.

Prophets connected God with the people, becoming bridges themselves—making interaction between both ends possible through the revealed word, of course, in the myth humanity loves the most.

Some linguists suggest an Indo-European root “pent”, meaning “to walk” or “to step,” linking the bridge to the act of walking over what previously had no ground—what was empty, where there was nothing, now there is a bridge.

Etymological Bridges Across Languages

In English, the word bridge comes from Old English “brycge”, which in turn derives from Proto-Germanic “brugjō”. This root is connected to the Proto-Indo-European “bherw”- or “bhrū”, meaning “beam” or “log.” The original idea was that of a “tree trunk” laid across a stream—a primitive solution that evolved into more complex structures. It shares lineage with words like beam and mast, suggesting a connection to support and elevation.

In German, “Brücke” comes from Old High German “brucca”, and Middle High German “brücke” or “brügge”. Its root, “brugjō”, is shared with English and Dutch "brug." and traces back to the same Indo-European root “bhrū”-.

In older dialects, “Bruck” also referred to wooden platforms or benches near ovens, reinforcing its origin as a wooden structure for crossing or supporting.

In Russian, the word “мост” (most) is linked to the verb “метать” (“to throw”), suggesting the idea of something cast or laid across a void. It comes from Proto-Slavic “mostъ”, possibly tied to the Indo-European “mazdo-s”, a root also present in Latin malus "pole" and English "mast."

In Old Russian, “мостъ” also meant roadway, platform, or ship deck, expanding its meaning as a surface for transit.

In Chinese, the character for bridge is 桥 "qiáo", written traditionally as 橋. It combines the radical 木 "mù: wood" with 喬 "qiáo: elevated," visually representing a "raised wooden structure."

The character appears in oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), evolving through clerical and regular script styles. It is used both literally and metaphorically: especially in diplomacy, where it symbolizes "connection between peoples."

In Japanese, the word 橋 "hashi" shares the same character as Chinese, imported through classical Chinese influence. The radical 木 "wood" signals its original material. The native reading is "hashi," and the character is deeply embedded in Japanese culture. Japan’s mountainous and riverine geography fostered a rich tradition of bridges—both: physical and spiritual.

In Shinto, sacred bridges like 神橋 (shinkyō) serve as portals between worlds.

Conceptually, 架橋 (kakehashi) is used to describe “bridging cultures or ideas."

In African languages, the concept of “bridge” often existed functionally before it existed linguistically.

In proto-Bantu languages like Kikongo, terms such as kasimba "water hole" and kandungu "barrel or floating structure" suggest early forms of "crossing or support."

Among ancient Kongo peoples, bridges were made of woven vines, fallen logs, or suspended platforms—acts of engineering without formal names.

In ancient Egyptian (Afroasiatic language family), no direct word for “bridge” is recorded, but terms like w3t "wat, pathorway" and ḥr "her: above or over" imply the concept of "crossing or elevation."

Architecturally, ramps and platforms were used, but bridges as we know them were rare. Symbolically, however, the idea of crossing—especially into the afterlife—was central to Egyptian cosmology.

The bridge that was offered, and the edge that refused to hold it

In 2013, during early discussions about China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), President Xi Jinping reportedly told U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry that American participation in the project was welcome.

Kerry, in deep regret, shared this with Professor John Thornton, who later revealed that before the delegation returned to Washington, Treasury Secretary Jacob Joseph Lew ordered him the rejection of the possibility, arguing a potential strategic entanglement.

Kerry later called it “the single biggest missed opportunity of my life.”

The BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) went on to become the largest infrastructure initiative in history, connecting over 150 countries and reshaping global trade, diplomacy, and influence.

This moment—when a bridge was offered and refused—mirrors the allegorical tribunal in our words. It wasn’t just a policy decision. It was a symbolic turning point, where the possibility of co-authorship in a new global chapter was declined.

So, it seems the issue never reached Obama and the strategic, open option for cooperation and partnership with China had died before it was born.

I'm sharing this story, said Thornton because if you read the details of the Initiative today, you would think it was a malicious Chinese tactic to control the world, which it isn't.

It is exactly what it claims to be: 'Extending a development model to all countries with five core characteristics:

- Peaceful world,

- Common prosperity,

- Harmony between man and nature,

- Openness and inclusivity, and

- Pursuit of green and low-carbon development.'

[The Xi Jinping You’ve Never Heard Of—Revealed by Former Goldman Sachs President John Thornton. Global Insight Hub - How an American Official Helped Preserve China’s Belt and Road Initiative.]”

The Architecture of Connection and the Politics of Refusal

Building bridges is an act of union. It is the will to connect what is distant, to overcome the void, to defy isolation. But refusing to build—or worse, destroying what has already been built—is not a neutral act. It is a declaration. It says: “I do not wish to meet you halfway. I do not wish to be connected.”

In geopolitical terms, the refusal to build bridges has consequences. It leads to fragmentation, confrontation, and loss. When one side offers its shore and the other withdraws, the result is not equilibrium—it is rupture. And rupture, unlike tension, is not a state of possibility. It is a state of injury.

The decision not to collaborate, not to associate, not to co-create, is often justified by invoking strategic priorities: influence, autonomy, security. But when these priorities come at the cost of the people’s well-being—when they sacrifice employment, stability, and dignity—then the refusal becomes more than a miscalculation. It becomes a transgression.

Some argue that collaboration with authoritarian regimes risks legitimizing their practices. But what of the authoritarianism within? What of the violations of constitutional order, the disregard for justice, the moral decay that goes unpunished—and even rewarded with political power? If bridges are denied abroad for fear of tyranny, why are they not built at home to restore integrity?

And what of the so-called “debt trap” diplomacy? China is accused of using infrastructure to ensnare nations in dependency. Yet for decades, institutions like the IMF and World Bank have imposed structural reforms that hollowed out economies and deepened inequality. If the trap is unacceptable when laid by others, why is it tolerated when laid by ourselves?

The Judgment of the Bridge

This unique bridge between China and the United States was never built, not because of a lack of planning but because of overcalculation and pure malice on the part of the latter. Today, the architects are summoned—not for what they constructed, but for what they chose not to raise. The people, from the shore, demand to know: who decided that the crossing was not worth it?

In this tribunal of memory, the bridge itself speaks. It does not accuse—it laments. It was drawn in dreams, whispered in chats, and welcomed in the win-win world. But it was never walked. And so, the void prevailed. Not because it was impossible, but because it was supposedly inconvenient or not strategic for the zero-sum world. Seriously?

The architects defend themselves. They speak of strategy, of sovereignty, of caution. They invoke the specter of dependency, the fear of legitimizing the other. But the people respond: “What legitimacy did we lose when our jobs disappeared? What sovereignty remains when our lives are priced beyond reach?”

The bridge, silent now, listens. It knows it was more than a structure—it was a possibility. A chance to meet, to trade, to learn, to heal. Its absence is not just a missed opportunity—it is a wound. And wounds, when ignored, become scars that shape generations.

Narrative Reflection

This scene is not fiction—it is allegory. It is the symbolic rendering of a historical moment when connection was offered and refused. It is the echo of decisions made from a ruling mindset in need of transformation, whose consequences ripple through markets, homes, and hearts.

Bridges are not neutral. They are declarations. To build is to say: “I believe in the possibility of union.” To refuse is to say: “I accept the permanence of division.”

Thus, the judgment is not about blame, but about responsibility. Who will assume responsibility for the chasm that separates and divides? Who will answer for the misunderstandings between the shores that would be resolved with a bridge?

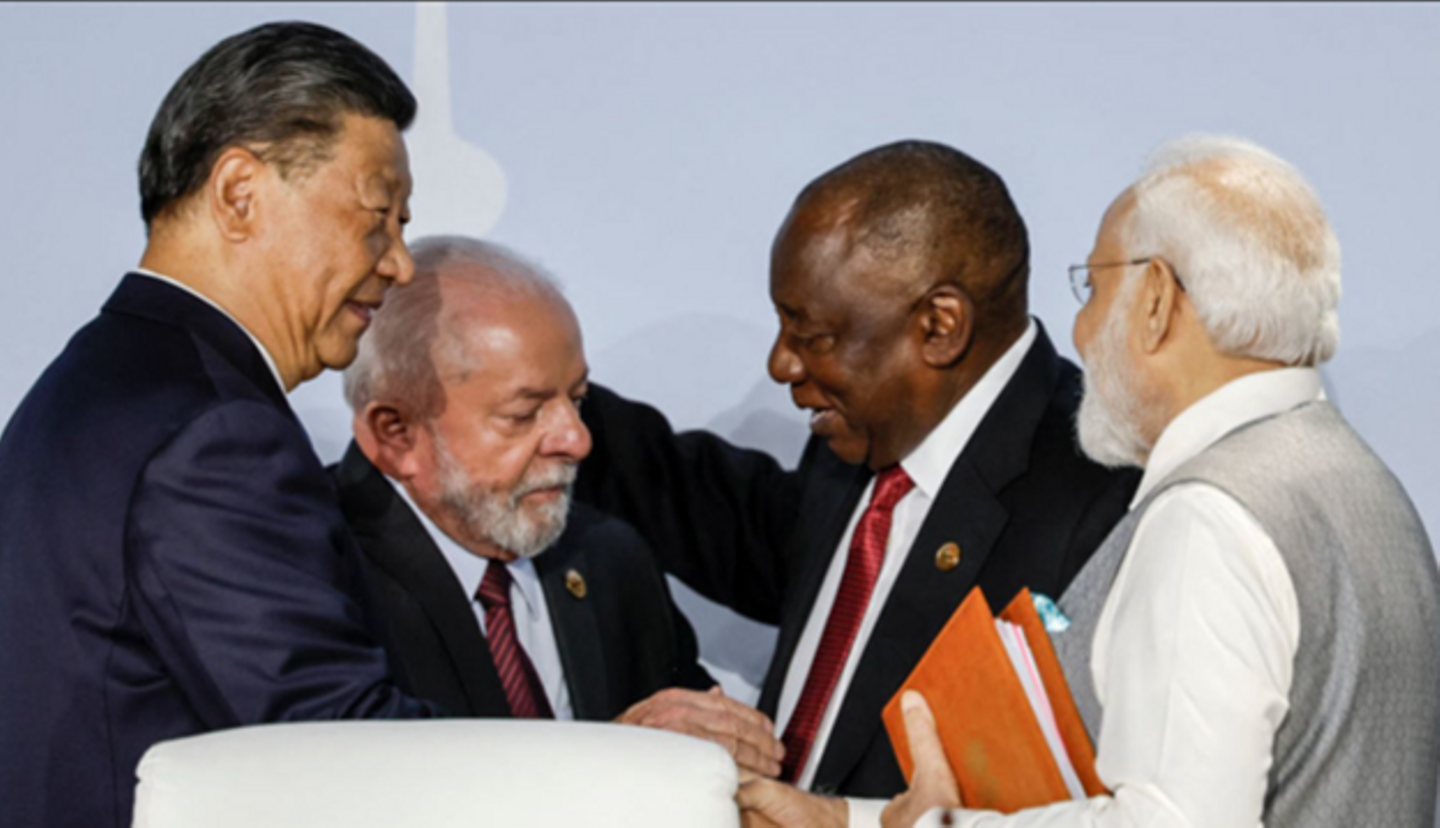

BRICS & SCO: The Bridge Builders

BRICS is an international political and economic association and forum established as a multipolar alternative. The founding members and its development potential, evident in 2000—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—added South Africa in 2010.

Currently, its GDP is 44% of global GDP and is growing.

The list of "Bridges and More Bridges," or, in other words, multi-billion-dollar megaprojects scheduled for the whole century, duly financed, is endless: energy, roads, research and development, infrastructure, ports, etc. Information on this is easy to find, but I want to share a verifiable anecdote about the spirit that prevails among these bridge builders.

It is said that at one of the recent SCO conferences, Vladimir Putin told Xi Jinping that Russian films were not selling well in China. The Chinese president suggested they make one together. Russian Culture Minister Olga Lyubimova played a public role in this, and during this year's SCO Film and Television Week Chinese officials expressed optimism. Minister of Culture Sun Yeli and the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) assumed the project's continuity.

Just imagining that your films will reach a market of 1.4 billion people, twice the size of the G7, makes one appreciate the benefits of initiating, nurturing, and multiplying bridges. The film is called "Red Silk" in Spanish, "Red Silk" in English, "Mr. Red Carpet" in Chinese, and it is the same in Russian as it is in Chinese.

It premiered in Russia on February 14, 2025 in honor of Valentine's Day. It also opened in China on March 10, coinciding with the closing of the Lianghui (Chinese: 两会), the annual meeting of the National People's Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), and International Women's Day. Its box office gross is estimated to be around US$51.5 million.

Epilogue: The Bridge as Memory

Before the bridge is built, there is silence. Before the first beam is laid, there is longing. And when the bridge is refused, there is memory.

Memory does not forget the offer. It remembers the hand extended, the plans drawn, the words spoken. It remembers the moment when connection was possible—and denied.

Bridges are not made of stone alone. They are made of will, of vision, of courage. They are made of the belief that the other shore is worth reaching.

And when they are not built, the void remains. Not as emptiness, but as testimony. A testimony to what could have been—and what was chosen instead.

Let this bridge, even in absence, speak. Let it remind us that every refusal is a decision. And every decision leaves a trace.

See you in the next article.

Sofocles Moran. September 12, 2025 (Updated December 14, 2025)

Those who favor building bridges will win, while those who oppose them will lose.